Originally posted on Space in Africa, here.

In June 2020, 146 participants from 33 countries participated in the GEO indigenous Hack4covid event. In this series, we will profile the four winning teams from the contest and their projections.

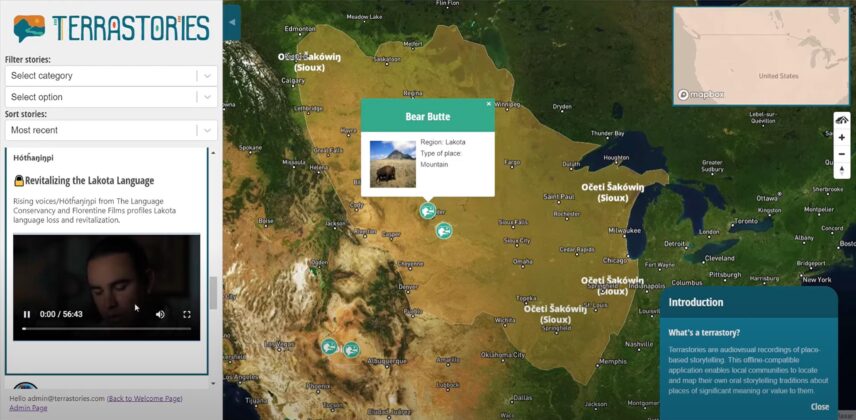

One of the winning ideas is the Terrastories map, which aims to help in the transmission of knowledge from the Elders to the youths of Rosebud Sioux.

James Rattling Leaf Sr. from the Rosebud Sioux Tribe in South Dakota posted a challenge that he termed Lapi Wowapiin in his native Lakota language, translating to “to write something for a purpose”. The challenge called for an app that will support the transmission of knowledge between the Elders and the youth while advancing the use of the Lakota language via digital stories that have a connection with the landscape.

Rudo Kemper picked up the challenge because it was sympathetic to his own experience and the work currently being done by his team. The Amazon Conservation Team (ACT) has been stewarding the creation of an open-source geo-storytelling tool called Terrastories, which can be used for mapping stories that have a connection with the landscape as well as shares many of the same values that the Lapi Wowapi challenge called for, such as advancing the native language, building a language repository by contributions, creating a virtual intergenerational community, and enhancing cultural values.

In this interview, Rudo tells us about the project…

Can you give us an overview of what the Terrastories: Lakota Makha project is about?

During the GEO Indigenous COVID-19 Hackathon 2020 event, James Rattling Leaf Sr. from the Rosebud Sioux Tribe posed a challenge that he called Lapi Wowapi in his native Lakota language, meaning “to write something for a purpose.” Catalyzed by the COVID-19 situation to think deeply about the critical role the Elders play in the community, the challenge called for an app that will support the transmission of knowledge between the Elders and the youth whilst advancing the use of the Lakota language via digital stories that have a connection with the landscape.

I saw the challenge and thought that it really resonated with some of the work my organization (the Amazon Conservation Team) has been doing with indigenous peoples in South America, who face similar struggles. Together with a team of volunteer developers, ACT has been stewarding the creation of an open-source geo-storytelling tool called Terrastories, which can be used for mapping stories that have a connection with the landscape, and shares many of the same values that the Lapi Wowapi challenge called for, such as advancing the native language, building a language repository by contributions, creating a virtual intergenerational community, and enhancing cultural values.

So, I decided to build Terrastories for the Lakota to show James Rattling Leaf Sr. what the application can do for his community. “Lakota makȟá” means Lakota lands in the native language. For this hackathon, I adapted it to the North American landscape by adding Lakota images, mapping data, and the video stories that James Rattling Leaf Sr. posted in his challenge, as a demonstration of how it could work for the Rosebud Sioux. This build of Terrastories can be used further to add cultural mapping data and place names, and recordings of elders telling stories about the land.

In what way has the Hack4COVID event contributed to the overall objectives of the Terrastories: Lakhota Makha project?

The COVID-19 Hackathon event enabled us to see clearly that indigenous communities in North America are facing the same challenges as communities in South America, and indeed also in Africa and elsewhere across the globe. We built Terrastories with a similar framing in mind: for example, the application works entirely offline, because indigenous communities across the world face similar issues with a lack of internet access, and wish to have complete sovereignty and control over their data. In this case, we saw that the Lakota / Rosebud Sioux tribe face almost exactly the same difficulties with the transfer of place-based knowledge and stories from the Elders to the younger generation, with the compounding threat that COVID-19 poses for community wellbeing and to the Elders in particular. Without the GEO hackathon, we would not have been able to learn about these difficulties in the Lakota communities.

This is quite ironic considering that the hack-a-ton was COVID-19 inspired, but has the pandemic in any way affected the progress of your project?

Because of COVID-19, the Amazon Conservation Team can’t travel to any of the communities that we partner with. Instead, we are doing what we can to coordinate the sending of biosafety materials, humanitarian aid, and communications in the native language to help the communities fight and abate the spread of COVID-19. The work we are doing around mapping place names and recording oral histories has come to a standstill, which is troublesome because it is the community Elders who face the most risk.

Are there any unique challenges this project is facing?

As mentioned, like everyone else our entire workflow has switched to a remote format, and so we can’t reach out to the community members on the ground. This is challenging because some of the communities don’t have internet access (which is the whole reason why we build Terrastories to be offline compatible).

However, we are trying to figure out a remote workflow with the youth who can continue to document their communities’ storytelling traditions, and contribute to the intergenerational transmission of knowledge, in spite of – and indeed also because of – these trying times that we find ourselves in.

What are the future projections you have for the Terrastories: Lakota Makha project?

The Terrastories team is ready and hopeful to continue working with James Rattling Leaf, Sr. and his community on the Lakota makȟá project, and are eager to help any other communities across the globe use the application to map their own place-based stories! If anyone is interested in using the application or help contribute to the open-source code, please visit https://terrastories.app.

Are there any recommendations or advice you can give as a participant in Africa’s space sector, towards the encouragement of more investors and innovators in the sector?

I primarily work in South America, but I’m always very impressed when I come across open-source geospatial and data collection tools developed in Africa, such as the Sapelli tool for remote data collection in contexts where not everyone is fully literate, humanitarian mapping initiatives such as Map Kibera and Humanitarian OpenStreetMap’s work in the continent, and the TIMBY on-the-ground reporting and storytelling toolkit.

I am a big believer in regional cross-pollination and mutual learning from each others’ experiences in different parts of the world, and I encourage potential donors to invest in the great innovations coming out of Africa’s geospatial sector so that the rest of the world can learn, benefit and also collaborate. One of the other GEO Indigenous COVID-19 hackathon submissions that won the first prize is a perfect exemplification of this vision: the Visibilidade App made for Brazilian quilombola communities, developed by a technologist from Kenya and an epidemiologist from Sudan. A wonderful inspiration and example for us all to follow.